CUSHING'S SYNDROME & DISEASE INDEX

What are Cushing’s Syndrome and Cushing’s Disease?

RARE CONDITION

Cushing’s syndrome is a rare condition that is the result of too much of the hormone cortisol in the body. Cortisol is a hormone normally made by the adrenal glands, and it is necessary for life. It allows people to respond to stressful situations such as illness and has effects on almost all body tissues.

It is produced in bursts, most in the early morning, with very few at night.

When too much cortisol is made by the body itself, it is called Cushing’s syndrome, regardless of the cause. Some patients have Cushing’s syndrome because the adrenal glands have a tumor(s) making too much cortisol. Other patients have Cushing’s syndrome because they make too much of the hormone ACTH, which causes the adrenal glands to make cortisol. When the ACTH comes from the pituitary gland, it is called Cushing’s disease.

Cushing’s syndrome is fairly rare. It is more often found in women than in men and often occurs between the ages of 20 and 40.

What Causes Cushing’s Syndrome and Cushing’s Disease?

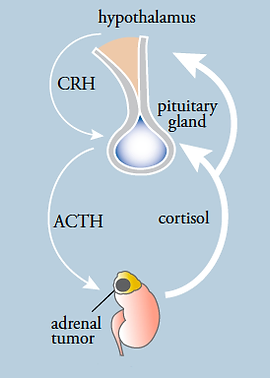

THE ADRENAL GLAND MAKES TOO MUCH CORTISOL

Cushing’s syndrome can be caused by medication or by a tumor. Sometimes, there is a tumor of the adrenal gland that makes too much cortisol. It may also be caused by a tumor in the pituitary gland (a small gland under the brain that produces hormones that, in turn, regulate the body’s other hormone glands).

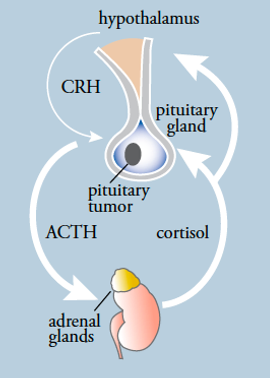

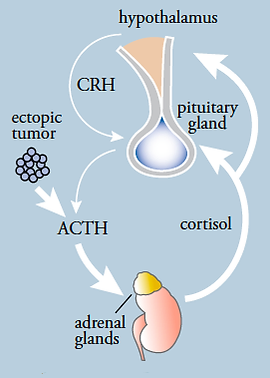

Some pituitary tumors produce a hormone called adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the adrenal glands and causes them to make too much cortisol. This is termed Cushing’s disease. ACTH-producing tumors can also originate elsewhere in the body, and these are referred to as ectopic tumors.

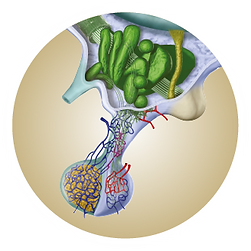

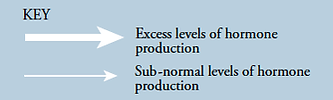

See below for an illustration of the differences between these three situations. It is important to note that pituitary tumors are almost never cancerous.

SCENARIO 1

In Cushing’s disease, a pituitary tumor makes ACTH, which stimulates adrenal gland production of cortisol. High cortisol levels inhibit CRH secretion and ACTH secretion from normal pituitary cells.

SCENARIO 2

In ectopic ACTH secretion, a non-pituitary tumor makes ACTH, which stimulates adrenal gland production of cortisol. High cortisol levels inhibit CRH secretion and ACTH secretion from normal pituitary cells.

SCENARIO 3

In primary adrenal disease, the adrenal glands independently make too much cortisol. High cortisol levels inhibit CRH secretion and ACTH secretion from normal pituitary cells.

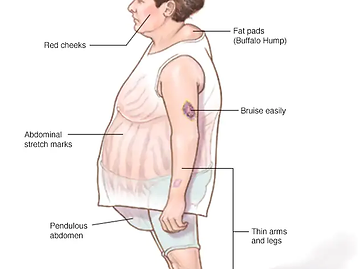

What are the Symptoms of Cushing’s Syndrome?

MOST COMMON SYMPTOMS

The main signs and symptoms are shown in Table 1. Not all people with the condition have all these signs and symptoms. Some people have few or “mild” symptoms - perhaps just weight gain and irregular menstrual periods. Other people with a more “severe” form of the disease may have nearly all the symptoms.

The most common symptoms in adults are weight gain (especially in the trunk, and often not accompanied by weight gain in the arms and legs), high blood pressure (hypertension), and changes in memory, mood, and concentration. Additional problems, such as muscle weakness, arise because of the loss of protein in body tissues.

TABLE 1. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF CUSHING'S SYNDROME

| COMMON FEATURES |

|---|

| Weight Gain |

| Hypertension |

| Poor Short-term Memory |

| Irritability |

| Excess Hair Growth (Women) |

| Red, Ruddy Face |

| Extra Fat Around Neck |

| Round Face |

| Fatigue |

| Poor Concentration |

| Menstrual Irregularity |

| LESS COMMON FEATURES |

|---|

| Insomnia |

| Recurrent Infection |

| Thin Skin and Stretch Marks |

| Easy Bruising |

| Depression |

| Weak Bones |

| Acne |

| Balding (Women) |

| Hip and Shoulder Weakness |

| Swelling of Feet/Legs |

| Diabetes |

Diagnosis

HOW IS CUSHING'S SYNDROME DIAGNOSED?

Because not all people with Cushing’s syndrome have all signs and symptoms, and because many of the features of Cushing’s syndrome, such as weight gain and high blood pressure, are common in the general population, it can be difficult to make the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome based on the symptoms alone.

As a result, doctors use laboratory tests to help diagnose Cushing’s syndrome and, if that diagnosis is made, go on to determine whether it is caused by Cushing’s disease or not. These tests determine if too much cortisol is made spontaneously or if the normal control of hormones isn’t working properly.

Cortisol Measurements

The most commonly used tests measure the amount of cortisol in the saliva or urine. It is also possible to check whether there is too much production of cortisol by giving a small tablet called dexamethasone that mimics cortisol. This is called a dexamethasone suppression test. If the body is regulating cortisol correctly, the cortisol levels will decrease, but this will not happen in someone with Cushing’s syndrome.

These tests are not always able to definitively diagnose Cushing’s syndrome because other illnesses or problems can cause excess cortisol or abnormal control of cortisol production. These conditions that mimic Cushing’s syndrome are called ‘pseudo-Cushing’s states’ and include the conditions shown in Table 2. Because of the similarity in symptoms and laboratory test results between Cushing’s syndrome and pseudo-Cushing’s states, doctors may have to do a number of tests and may have to treat conditions that might cause pseudo-Cushing’s states – such as depression – to see if the high cortisol levels become normal during treatment. If they do not, and especially if the physical features get worse, it is more likely that the person has true Cushing’s syndrome.

TABLE 2. PSEUDO-CUSHING'S STATES

| PSEUDO-CUSHING'S STATES |

|---|

| Strenuous Exercise |

| Sleep Apnea |

| Depression and Other Psychiatric Disorders |

| Pregnancy |

| Pain |

| Stress |

| Uncontrolled Diabetes |

| Alcoholism |

| Extreme Obesity |

What Tests are Needed Specifically to Diagnose Cushing’s Disease?

ACTH MEASUREMENTS

Patients with adrenal causes of Cushing’s syndrome have low blood ACTH levels, and patients with other causes of Cushing’s syndrome have normal or high levels. A doctor can diagnose too much ACTH by measuring its level in the blood.

Inferior Petrosal Sinus Sampling (IPSS)

The best test to distinguish an ACTH-producing tumor in the pituitary from one in another part of the body is a procedure called inferior petrosal sinus sampling or IPSS. This involves inserting small plastic tubes into both the right- and left-sided veins in the groin (or neck) and threading them up to the veins near the pituitary gland. Blood is then taken from these locations and also from a vein not connected to the pituitary gland.

During the procedure, a medication that increases ACTH levels from the pituitary is injected. By comparing the levels of ACTH produced close to the pituitary gland in response to the medication with those produced by other parts of the body, a diagnosis can be made.

Further Tests

Other tests are used to diagnose Cushing’s disease, such as dexamethasone suppression and corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation tests. However, these are not as reliable in distinguishing between the causes as IPSS. A doctor may want to do multiple tests to confirm the results. It is also possible to visualize the pituitary gland using a process called magnetic resonance imaging (>MRI). This involves an injection of an agent that will help the tumor to show up on the MRI scan. If this test shows a definite tumor above a certain size and the CRH and dexamethasone test results are compatible with Cushing’s disease, IPSS may not be needed. However, up to 10% of healthy people have an abnormal area on their pituitary, consistent with a tumor. Therefore, the presence of an abnormality alone is not diagnostic of Cushing’s disease. Also, in about 50% of patients with Cushing’s disease, the tumor is too small to be seen. Thus, the absence of a tumor on an MRI scan does not necessarily exclude Cushing’s disease.

Self-Management

WHAT CAN I DO TO HELP MANAGE

CUSHING'S DISEASE?

Look after your general health, eat well, and exercise regularly. However, because bones may weaken, avoid high-impact exercise or sports that involve falls to reduce the chance of a bone break.

- Ask your doctor if you are getting enough calcium and vitamin D in your diet. These may help strengthen the bones.

- Give up smoking. This decreases the chance of having problems with surgery.

- Don’t drink too much alcohol.

- Make sure you take the full course of any medicines that your doctor may give you.

- Do go back and see your doctor if any of your symptoms worsen.

- After a pituitary surgery, if you feel sick or suffer flu-like symptoms, contact your doctor.

Treatments

WHAT ARE THE TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR

CUSHING'S DISEASE?

The only effective treatments for Cushing’s disease are to remove the tumor, reduce its ability to make ACTH, or remove the adrenal glands. There are other complementary approaches that may be used to treat some of the symptoms.

For example, diabetes, depression, and high blood pressure will be treated with the usual medicines used for these conditions. Also, doctors may prescribe additional calcium, vitamin D, or other medicine to prevent thinning of the bone.

Pituitary Tumor Removal by Surgery

Removal of the pituitary tumor by surgery is the best way to treat Cushing’s disease. This is recommended for those who have a tumor that does not extend into areas outside of the pituitary gland and who are well enough to have anesthesia. This is usually carried out via the nose or upper lip and through the sphenoid sinus to reach the tumor. This is known as transsphenoidal surgery and avoids having to get to the pituitary via the upper skull. This route is less traumatic for the patient and allows quicker recovery.

Removing only the tumor leaves the rest of the pituitary gland intact so that it will eventually function normally. This is successful for 70–90% of people when performed by the best pituitary surgeons. The success rates reflect the surgeon's experience performing the operation. However, the tumor can return in up to 15% of patients, probably because of incomplete tumor removal at the earlier surgery.

Radiosurgery

Other options for treatment include radiation therapy to the entire pituitary gland or targeted radiation therapy (called radiosurgery) when the tumor is seen on MRI. This may be used as the only treatment, or it may be given if pituitary surgery is not completely successful. These approaches can take up to 10 years to have full effect. In the meantime, patients take medicine to reduce adrenal gland production of cortisol. One important side effect of radiation therapy is that it can affect other pituitary cells that make other hormones. As a result, up to 50% of patients need to take other hormone replacement within ten years of the treatment.

Adrenal Gland Removal by Surgery

Removal of both adrenal glands also removes the ability of the body to produce cortisol. Since adrenal hormones are necessary for life, patients must then take a cortisol-like hormone and the hormone florinef, which controls salt and water balance, every day for the rest of their lives. An experienced pituitary- or neuro-endocrinologist can help to decide the best course of treatment.

Drug Treatments

While some promising drugs are being tested in clinical studies, currently available medications to reduce cortisol levels, when given alone, do not work well as a long-term treatment. These medicines are most often used in conjunction with radiation therapy.

After Treatment

HOW CAN I EXPECT TO FEEL AFTER TREATMENT FOR CUSHING'S DISEASE

Most people will start to feel gradually better after surgery, and the hospital stay may be quite short if there are no complications. It can take some time to feel completely back to normal, to lose weight, to regain strength, and to recover from depression or loss of memory.

It is important to remember that high cortisol levels physically change the body and brain, and these changes may reverse quite slowly. This is a normal feature of the recovery period, and patience is definitely a virtue here.

Following Pituitary Surgery

After successful pituitary surgery, cortisol levels are very low. This can continue for 3–18 months after surgery. These low levels of cortisol can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, aches and pains, and a flu-like feeling. These feelings are common in the first days and weeks after surgery as the body adjusts to the lower cortisol levels. Doctors give people a cortisol-like medicine until recovery of the pituitary and adrenal glands is either well underway or complete.

Hydrocortisone or prednisone is usually used for this purpose. Doctors monitor the recovery of the pituitary and adrenal glands by measuring morning cortisol values or by testing the ability of the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol in response to an injected medication similar to ACTH.

Until the pituitary and adrenal glands recover, the body does not respond normally to stress – such as illness – by increasing cortisol production. As a result, people who suffer from ‘flu,’ fever, or nausea may have to double the oral dose of glucocorticoid when they are sick. However, this increased dosage should only be used for 1–3 days. On occasion, people can suffer vomiting or severe diarrhea that prevents them from absorbing the glucocorticoids taken by mouth.

In this situation, it may be necessary to receive injections of dexamethasone or another glucocorticoid and seek emergency medical care. Patients should wear a MedicAlert bracelet until glucocorticoid replacement is stopped.

If it is necessary to have a prolonged increase in hydrocortisone, a doctor should evaluate this need, and a ‘tapering’ regimen may be needed to reduce the dose back to the daily requirement.

Following Adrenal Gland Surgery

People who have had their adrenal glands removed will have to take a glucocorticoid (like cortisone) and mineralocorticoid fludrocortisone (brand-name Florinef) for the rest of their lives. There may be a concern that the pituitary tumor will enlarge, so MRI imaging of the pituitary gland may be done after this surgery. People whose adrenal glands have been removed may have initial symptoms that are similar to those after pituitary surgery, and they should take extra glucocorticoid during illness as described above and wear a MedicAlert bracelet.

It is important to note that if you are taking replacement cortisol, there may be a number of occasions when you need additional replacement. This can include stressful situations, such as surgical procedures – whether or not related to Cushing’s syndrome – dental procedures, and so on. You should discuss your specific condition with your endocrinologist and ensure you know what situations to look out for and what action to take.

Frequently Asked Questions

An endocrinologist is a physician who specializes in hormone disorders. Cushing’s syndrome and disease are fairly rare and often quite complex, and the best results can be expected when these are treated by a specialist endocrinologist, often together with a neurosurgeon.

The most common way to remove pituitary tumors is through the transsphenoidal approach. This involves entering the pituitary gland by making an incision in the back of the nose and approaching the pituitary gland through the sphenoid sinus. Using a microscope or endoscope, the surgeon will explore the pituitary gland, hopefully, find the tumor, and remove it.

Since these tumors are very small, it can be difficult to find them, and the gland can be damaged during the procedure. If this happens, other hormone functions can be lost. Since the pituitary gland controls the production of thyroid hormone, estrogen in women, testosterone in men, and growth hormone – in addition to ACTH – replacement therapy for these other hormones might be required. Also, if the posterior part of the pituitary is damaged, anti-diuretic hormone can be lost. This hormone is responsible for water reabsorption by the kidneys, and without it, patients urinate frequently and in large amounts (“diabetes insipidus”), leading to dehydration. This hormone can be replaced with a daily dose of a nasal spray or pill.

Since the pituitary gland is bordered by the optic nerves and carotid arteries, there is a very small risk that these structures could be damaged (less than 1%). However, if this were to happen, the patient could suffer visual loss or a stroke. The pituitary is separated from the spinal fluid by a thin membrane. If this membrane is damaged during the surgery, a spinal fluid leak can result. If spinal fluid leakage occurs and is undetected, a serious infection, meningitis, can result. Most surgeons take a small piece of fat from the abdominal wall to use as a plug to prevent this leakage from occurring. The risk of this happening is about 1%. Since the pituitary gland is involved in water and sodium balance, this can be affected transiently by the surgery as well, and your endocrinologist will monitor your sodium levels after the surgery. All of these risks are minimized in the hands of an experienced surgeon.

Direct effects of the surgery include nasal congestion and possibly headache. These symptoms will resolve after 1–2 weeks. If the operation is successful, however, the cortisol levels will drop dramatically. Patients can experience symptoms of cortisol withdrawal, which can include profound fatigue, and this can sometimes last for weeks or months after the surgery. If the operation is successful, the patient will have to take cortisol replacement until the remaining normal pituitary gland recovers (see below, n8).

Your endocrinologist will test your urine and/or blood and/or saliva cortisol levels a few days after the surgery. Usually, success can be determined within a few days of the operation.

Almost all of the symptoms of Cushing’s disease are reversible. When the cortisol levels drop, obesity improves, and appetite normalizes. Muscles and bones become stronger. Diabetes and hypertension improve. These effects may require many months.

A patient cured of Cushing’s disease should have very little, if any, measurable cortisol. Once the tumor has been removed completely, the rest of the pituitary gland is still suppressed (relatively "asleep"). It may take several months for the normal ACTH-producing cells to start functioning again. In the meantime, steroid replacement is necessary to protect against too little cortisol (adrenal insufficiency). In patients cured of Cushing’s disease, taking cortisol replacement is essential for life. At a later date, the need for continued steroid replacement is determined by blood tests. Most, but not all, patients who are cured of Cushing’s disease will not need steroids after a year is over and sometimes sooner. If a person has to take steroid replacement, he/she should wear a medical alert bracelet or necklace, which identifies the need for steroid treatment and extra dosing during acute sickness.

This is a common question and a very common problem. Cushing affects every system of the body; it causes problems gradually, particularly its effect on muscles and body fat. With Cushing's, muscles become thin and weak. It takes a long time for the body to "repair" itself, usually 9 to 12 months. It is quite common for patients to still feel weak and have achy muscles several months after successful surgery or successful radiation treatment. More positively, the problems with depression, concentration, and memory may improve fairly soon in successful pituitary surgery. Most patients have improvement in mood and depression six months after successful treatment. However, they are still frustrated that they are not “back to normal.” Unfortunately, the excess weight does not "magically" disappear - it takes time and a weight reduction diet to return to normal body weight. The important word here is patience. Occasionally, some patients may experience an increase in depression and anxiety after the cure of Cushing’s as the body re-adjusts to large changes in cortisol, going from very high to low levels.

There are a number of options if the initial transsphenoidal operation is unsuccessful. Sometimes, a second operation is recommended if no tumor was found during the initial operation. Alternatively, radiation therapy of the pituitary gland can be considered. Medical control of cortisol levels is required while awaiting the beneficial effects of radiation. Finally, the adrenal glands themselves can be removed. This stops the body from making any cortisol, and so the symptoms of Cushing’s disease resolve, although the pituitary tumor itself remains untreated. Choosing between these options requires a careful discussion between the patient, endocrinologist, and surgeon.

There are presently no approved medical treatments in the US for the pituitary tumors that cause Cushing’s. A new medication (Pasireotide, SOM230) has just been approved in Europe as a bi-daily injection for the treatment of Cushing’s disease. This medication is not yet available in the US. However, there are medications that can reduce cortisol production by the adrenal glands but do not have any effect on the pituitary overproduction of the hormone ACTH (the pituitary hormone that stimulates the adrenal glands to make too much cortisol). By blocking the production of cortisol by the adrenal glands, these medications can reduce many of the problems such as hypertension, weight gain, diabetes, tendency to infections, and depression. Ketoconazole (Nizoral) is a medication that reduces adrenal gland cortisol production. This medication is most often used in patients who are not cured of Cushing's after surgery, are too ill to be operated on, and need to have cortisol levels quickly lowered before surgery and while waiting for therapy to become effective in patients treated with radiotherapy. If a drug to lower cortisol is prescribed, careful monitoring is necessary to determine if the dose is effective (measure 24-hour urine cortisol level), to make sure it does not reduce cortisol to below normal (measure morning blood cortisol level), and to make sure there is no ill effect on the liver. This drug is usually given twice a day. Sometimes, when giving the exact amount of ketoconazole is difficult, a very small amount of a steroid, for example, dexamethasone, is used together with ketoconazole to keep the adrenal glands blocked down but to prevent the patients from having too little cortisol.

Another drug that may be used in patients who cannot tolerate ketoconazole is metyrapone. This medication blocks the production pathway of cortisol by the adrenal glands. It may stimulate ACTH from the tumor and, therefore, is not usually the first drug used unless ketoconazole cannot be given. This is difficult to obtain in the USA.

Another drug is called mitotane, but this is rarely used due to severe side effects.

Ketoconazole (Nizoral): The most common side effects are nausea and abnormalities in liver function. Before this medication is taken, a blood test should be measured to make sure there are no significant liver abnormalities. If the patient develops fatigue or jaundice, liver tests should be measured again, and the medication should be stopped immediately. If liver tests become abnormal, they usually return to normal after the ketoconazole is stopped. Other side effects include vomiting, abdominal pain, and itching. If a patient is on a stomach medication to reduce acid secretion, absorption of ketoconazole may be reduced. This problem may be solved by taking the medication with an acid beverage, such as Coca-Cola.

Metyrapone: the most common side effects are nausea and sometimes vomiting.